Click here to view image

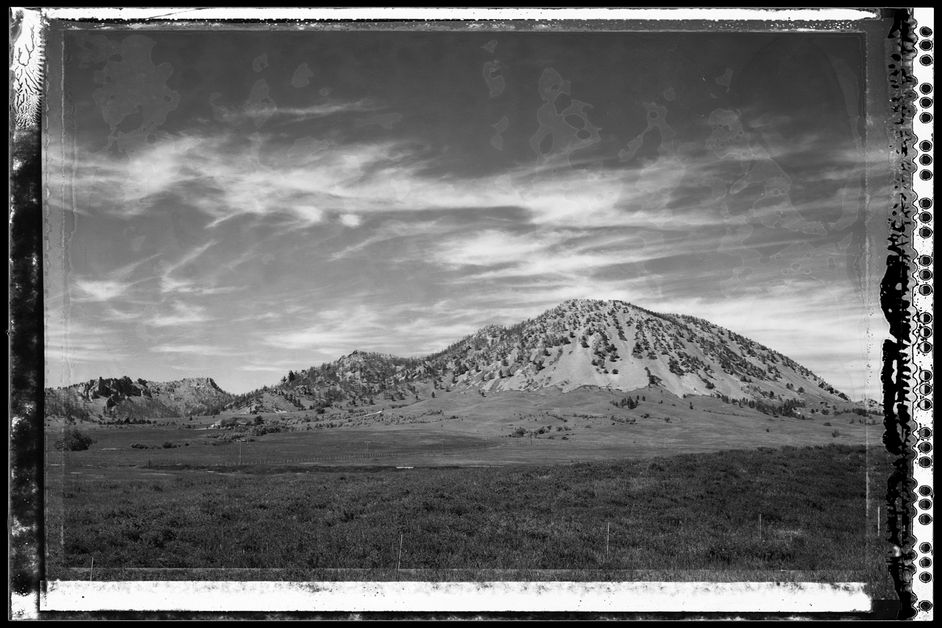

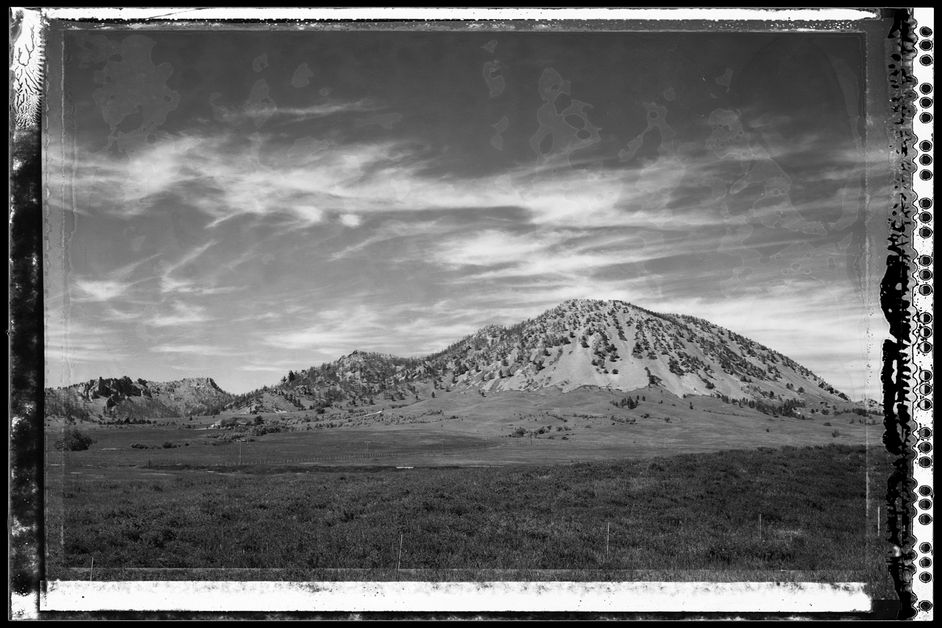

Medicine Wheel, Bear Butte, South Dakota

Click here to view image

Medicine Wheel, Bear Butte, South Dakota

Click here to view image

Scenic Overlook, Badlands, South Dakota

Click here to view image

Bear Butte Holy Mountain of the Lakota and the Cheyenne, South Dakota

Click here to view image

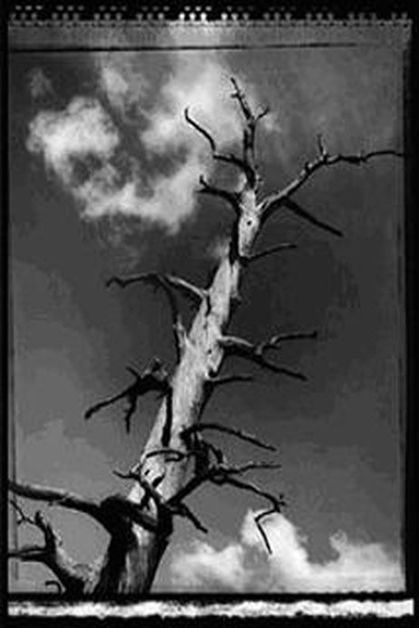

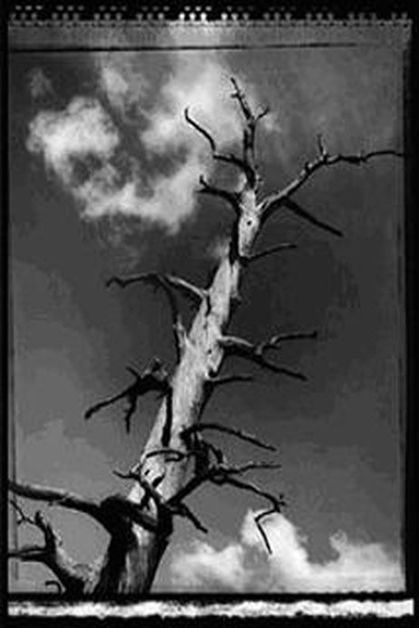

Ancient Tree, Black Hills, South Dakota

Click here to view image

Custer's battlefield, Montana

Click here to view image

Road to Red Cloud's grave, Pine Ridge, Sud Dakota

Click here to view image

Click here to view image

Road to the top of the Sheep Table, Badlands, South Dakota

Click here to view image

The display of the instruments

Click here to view image

Otaga Korin, Rinpa School, Japan, Edo period (1603-1868)

Fan

Fan in kekejiku format, ink, colours and gold on paper

The iris kakitsubata (杜若) stands out for its beautiful purple flowers with shades tending to blue. The falling sepals recall the ears of a rabbit and are mottled with white. Its leaves, resembling swords, can reach up to 70 cm. The kakitsubata blooms in the springtime.

This is a fan painted on paper, mounted like a kakemono (a roll to hang), datable 1711-1736. The blue irises are placed on a golden background, to show their preciousness: the background is an ocher cloud, sprinkled with crumbs of gold leaf; we perceive the limit of the cloud only at the right end, where we see a bluish-green pond. In it we can see some slight streaks that refer to golden spirals, on which the iris grows. These petals and leaves are outlined with a fine brush dipped on black ink. Moreover, Kōrin opts for a close-up of a fully open kakitsubata, whose falling sepals suggest an already advanced flowering, in contrast to the flower still in bud on the right.

Headquarters:

Municipality of Genoa - Palazzo Tursi

Via Garibaldi 9 - 16124 Genoa

C.F / VAT 00856920102